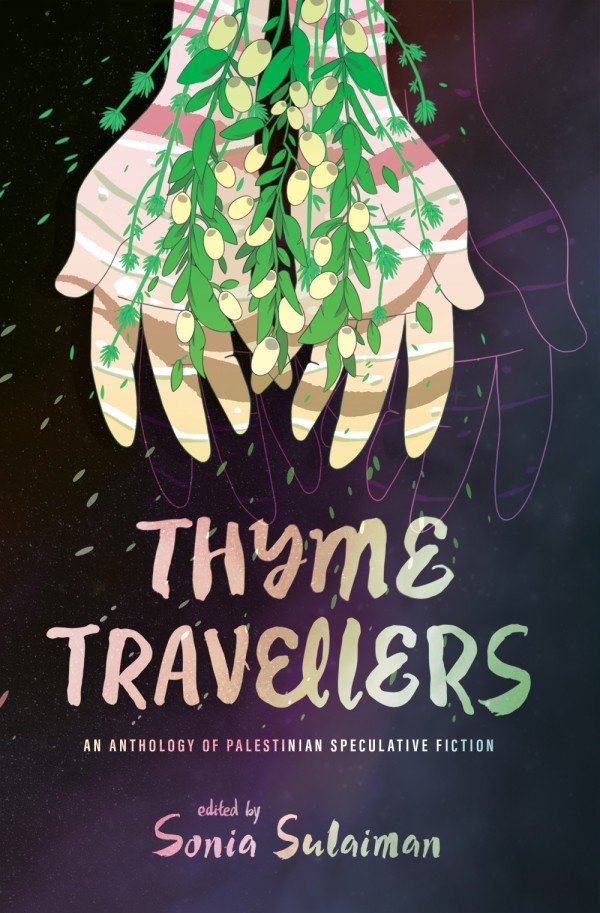

Thyme Travellers: An Anthology of Palestinian Speculative Fiction collects fourteen stories by new and established writers from the Palestinian diaspora. Edited by Sonia Sulaiman, these stories imagine new worlds and confront the reality of our own. Individually, these stories are thought-provoking and sincere. Together, they beautifully explore Palestinian identity and resistance, and offer readers a chance to reflect upon the present moment and what we want the future to look like.

The Coin follows a wealthy Palestinian woman who takes on a position as a teacher at an all-boys school in New York City. She is tastefully extravagant, chaotically in crisis, not a particularly good or moral person, and one of the most fascinating characters to emerge in contemporary fiction.

Ellen Chang-Richardson’s debut poetry collection Blood Belies is a tender and probing examination of how history can be traced through memory, mapping the orientation of the Asian-Canadian experience against the unyielding landscapes of “permafrost and / rust and dirty snow slush.”

The Last to the Party (Gooselane Editions, icehouse, 2024) is an honest and moving debut trade poetry collection by bpNichol Chapbook Award recipient, Chuqiao Yang. Yang navigates the complicated terrains of family, heritage, ancestry, identity, racism, belonging, friendship, grief, love, tenderness, heart, and ferocity, as the book moves from childhood to adulthood.

Stories are often an amalgamation of perspectives and a person’s unique connection to them, resulting from all the stories they’ve lived; Bird Suit navigates multiple perspectives and multiple stories, slowly stitching together a central story that many people hold a piece of.

The texture of faith in Theophanies soothes me, as it understands faith as flawed, ruptured, unruly and riotous. The cover begins our understanding of this faith, present in titles. I understand Theophanies as the combined Greek theos from θεός • (theós), meaning “god” or “divine”, and φαίνω (phaínō), concerning manifestation and appearance.

With its Lisa-Frank-esque, unicorn-bedecked cover, Sadie McCarney’s second poetry collection promises fun, irreverence, and whimsy. In that aspect, it certainly delivers, but behind the cotton-candy design also lies a deep dive into mental health, personal experience, and history that you might not expect.

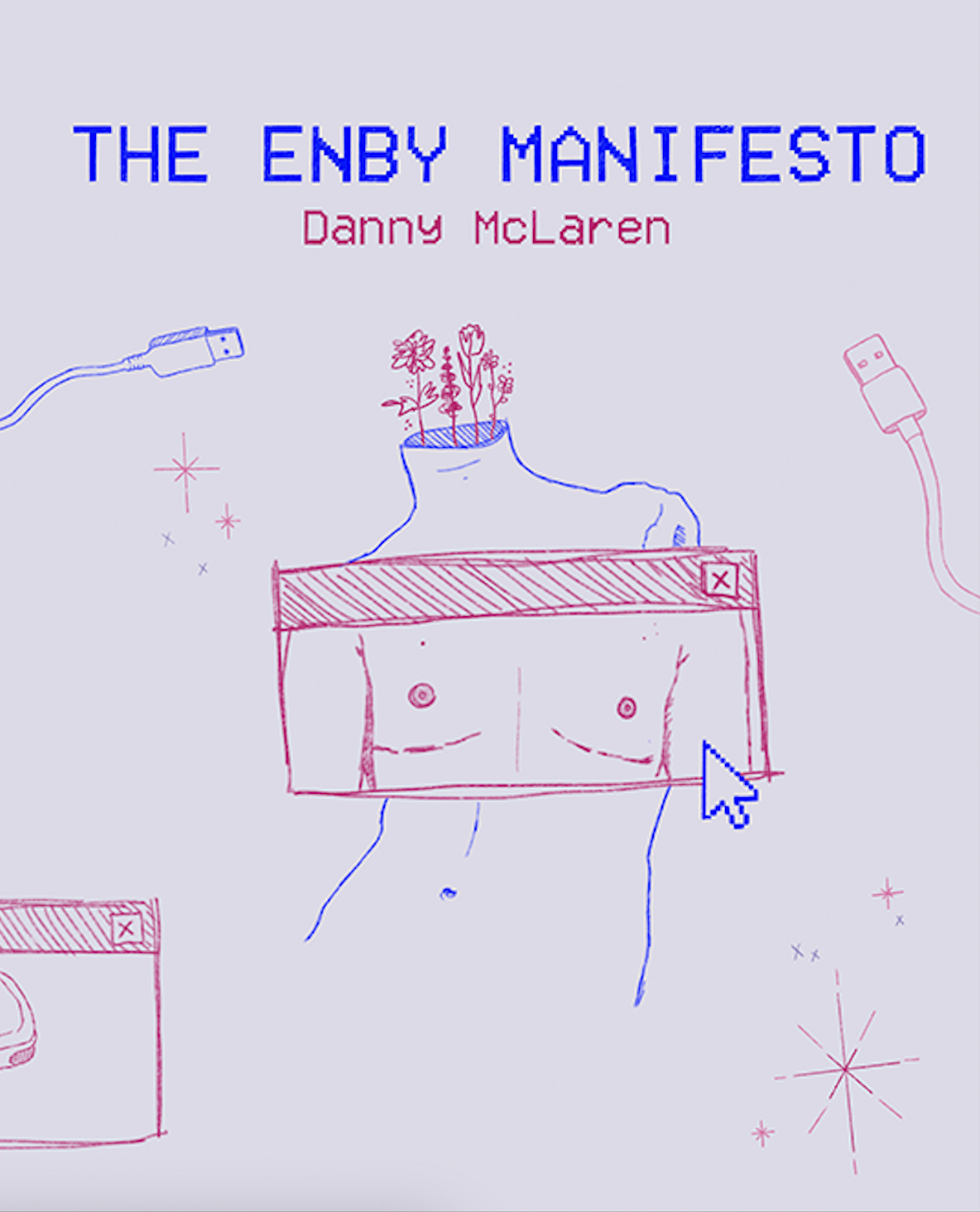

The power of McLaren’s wanting draws me in, confronting me with the necessity for a surgery that leads to (otherwise taken for granted) everyday freedoms, including commonplace acts like wearing loose fitting t-shirts and baring skin at the beach or pool, in what I imagine as normative public places.

Emily Osborne’s Safety Razor displays an assured poetic voice, more so than one might expect in a debut. This is quite possibly reflective of Osborne’s scholarly background, which includes a Masters (MPhil) in Old English and a PhD in Old Norse, both from Cambridge.

Hazel Jane Plante’s second novel Any Other City circumvents this tired narrative to paint a more complete picture of a trans woman musician becoming an artist, having lots of hot sex and healing from trauma.

Currin’s is a poetics with roots in the New York school, and which, Currin has transferred to the streets of Vancouver. Currin’s is a “local” poetry, local to this writer’s social, political, and artistic life in the City of Glass, variously described in the poems as rainy, foggy, mildewy, and musty.

hanna’s use of rich language to capture the inner narrative of her lived experience and matrilineal inquiry as a child of a single mother forced to migrate to Canada from Egypt in the 1970s evokes a visceral sense in the reader.

In her latest poetry collection Flyway, Sarah Ens creates a narrative about what we do to survive—what our instincts are to carry forward, amidst war, violence, oppression, displacement, loss, and grief.

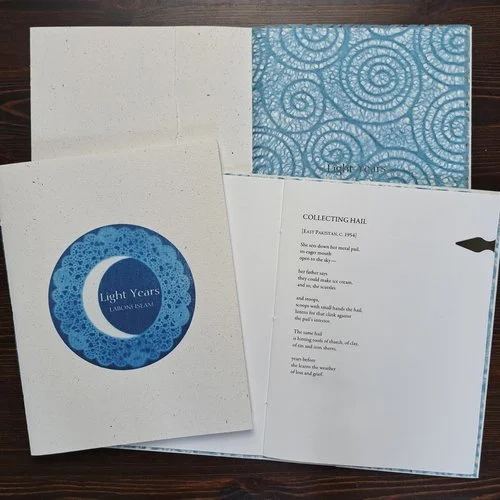

In the fall of last year, Baseline press debuted a new poetry line-up of four chapbooks, including Laboni Islam’s Light Years and Jodi Chan’s militant. I am lucky enough to sit down with these two works and explore their intermingled threads.

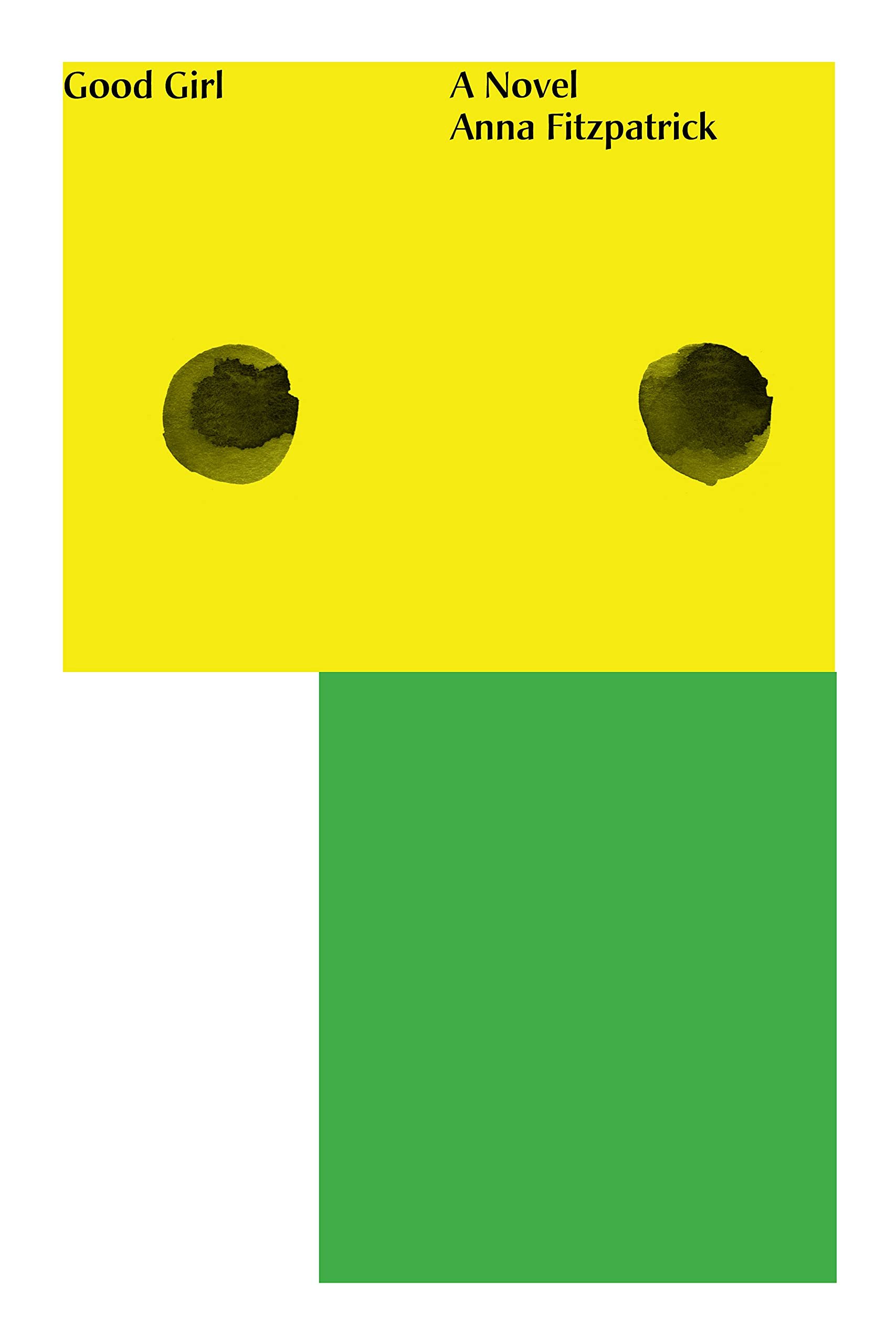

For readers looking for some literary smut, they will find it. However, they’ll also find so much more. For Lucy, the protagonist of Good Girl, this is her odyssey for real intimacy and what it means to be ‘good’: whether in bed, as a writer, as a daughter, or as a friend.

A powerful writing tactic Purcell excels at is offering layered and multiple meanings in a central or single muse of a poem. In “Earring,” Purcell uses the image on an earring to anchor the poem; however, the reader can understand that the poem is about much more than an ornamental piercing. Consider the line, “Your child coming home pierced, your voice / all the way through the wound / that never grows over.” (24). Purcell sets the scene so that we may understand the depth to this piercing: its relationality to family, coming out, and queerness and its visibility.

Standing in a River of Time by Jónína Kirton is an unrelenting memoir. Each chapter is comprised of a narrative section and a set of poems, focalized through a character, theme, time frame, or a series of events. It is also a heavy text, holding stories of death, abuse, violence, intergenerational trauma, and poverty.

In her debut poetry collection Orion Sweeping, Anne Marie Todkill attends to the consequences of human experiments and what we humans have made of our lives on Earth. Sectioned into fifths titled “Earth,” “Air,” “Familia,” “Loss Lessons,” and “Assisi Variations," respectively, the poems mostly fit to those themes, though the connections are sometimes indirect, even elusive.

Clayton collages these dream details together into something like meaning, something like a riddle, something like an escape room, in what becomes a compelling through-line linking each poem to the next. Dreams, after all, are a kind of serial publication, and so too does each poem in this collection feel like a new episode in a whirling, surreal narrative. What will the next episode bring—danger, or catharsis? Survival, or pain? The answer to the riddle, or only more riddles?

Gillian Sze’s latest collection, Quiet Night Think, takes its title from a famous poem by Li Bai. The first essay of this multi-genre work shares this title and focuses on Sze’s childhood obsession with understanding Li Bai’s poem, thus introducing many of topics this collection addresses—Chinese culture, language, translation, nostalgia, family—and setting the contemplative and introspective tone for the work.

The author has shared something with us so intimate that the reader feels as though they have walked into a moment they were not supposed to be privy to. The deliverance of this line holds so much weight — and as a diasporic person, it holds even more. The validation of this experience, one that many of the diaspora know deeply, is one that as a reader, I am grateful to have verbalized.

Parker’s clean and exacting writing, while excellent in her previous novels, soars to new heights in What We Both Know.

Tirelessly reckoning with the contradictions of living on occupied land, Phoebe Wang’s Waking Occupations aches towards a body that is unbounded by capitalistic notions of space and time. The poems in the collection examine what it means to recover a country that has already renounced you, and how to live within that doubleness.

How can you love a language you don’t remember, a city as full of ugliness as beauty, and a natural world that is in peril? How can you choose to honour parents who reject your dreams and seem to reject you in the process? In her debut collection, Pebble Swing, Isabella Wang accomplishes all this and much more by way of openness, observation and a unique delicacy.

Despite the fact that one of the collection’s central themes is grief, the book does not feel heavy. Rather, the weightlessness with which Wani pens these poems is indicative of the many ways we do not realize how grief can exist in the small pockets of life, and how its constant distribution makes it manageable to carry after all. The ways Wani intertwines narratives of grief into love or into religion disrupts the narrative that grief is all-consuming in its negativity; rather, Wani appears to pose the question: how can we have grief without love?

Written in four movements, the poems take you from emotional exhaustion through to journeys of recovery and reflection. The collection divides its time contemplating the loss of a mother, the anatomy of breakups, and the nature of middle-age. Within these overarching themes is a narrator standing both within the experiences, as well as just off to the side, evaluating their meaning.

The poems in Anna Van Valkenburg’s debut poetry collection Queen and Carcass are self-contained: each one a seed-grain splitting open, or maybe an egg, revealing bent and twisted new bodies, wet with life-giving substance. There was an HBO show, Carnivale, which aired in the early 2000s and depicted the lives of various members of a travelling carnival in the Dust Bowl during the Great Depression in the 1930s. Queen and Carcass brings to mind the quirks, characters, and magico-bleak atmosphere of that HBO showcase of surreal gifts.

Vivek Shraya’s work of nonfiction, People Change, focuses on themes of reinvention, transformation, and the myriad of ways in which a person may be driven to and experience change. Shraya does not leave a single stone unturned. She draws attention to the many moments of change that one may encounter in their lifetime, and analyzes the value of this process for our self-betterment and fulfillment.

A euphoric and euphonic ode to gardening, Sylvia Legris’s Garden Physic is a poetic tour de force that connects the passionate gardener to her ecological and linguistic milieus. The garden becomes a metaphor for our verbal habits, our lives and our loves, our ways of relating to one another and the living world we belong to.

Zehra Naqvi’s debut collection The Knot of My Tongue explores personal and generational calamities: domestic violence, a family’s displacement during the Partition, the Battle of Karbala. Writing about or within unspeakable violence is no simple task for a poet.