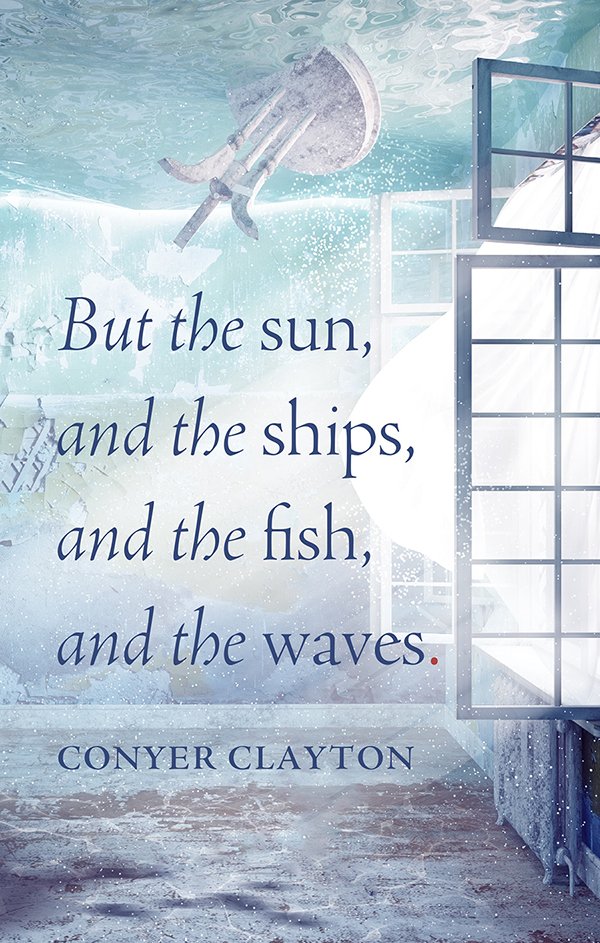

The Surreal Logic of Dreams: Review of Conyer Clayton’s But the sun, and the ships, and the fish, and the waves.

Conyer Clayton, But the sun, and the ships, and the fish, and the waves.

Anvil Press, 2022. $18 CAD.

Order a copy from Anvil Press.

Conyer Clayton’s latest full-length collection, But the sun, and the ships, and the fish, and the waves, is an expansion of one of her best chapbooks—a slim, baby blue volume chronicling the poet’s dreams titled Trust Only the Beasts in the Water. These dreams become expansive in their new home in this full-length, mapping a surreal landscape that feels unsettling and comforting by turns. Clayton collages these dream details together into something like meaning, something like a riddle, something like an escape room, in what becomes a compelling through-line linking each poem to the next. Dreams, after all, are a kind of serial publication, and so too does each poem in this collection feel like a new episode in a whirling, surreal narrative. What will the next episode bring—danger, or catharsis? Survival, or pain? The answer to the riddle, or only more riddles?

The first words of the first poem are perhaps the best introduction to the poet’s amalgamated dream world, feeling simultaneously like a comfort and a threat: “It ends” (9). These poems wrestle with inevitability: their logic ushers both reader and poet along its winding path, piloted by some greater narrative, the end of which we glimpse in the first line of the first poem. And yet how to get there? How to get out of there? Especially combined with Clayton’s sly penchant for second person—“You can’t turn around on a road like this” (9), “Do you even recall who you are?” (10), “You think you’re safe if the lights are on” (45)—reading this collection feels as though the reader and poet are watching the poet’s avatar together, a character in a surrealist film who barrels along her set path over and over, unable to heed anyone’s advice from her position in the dream world.

The unsettling and unsettled logic of this dream world is emphasized by the title of the collection: But the sun, and the ships, and the fish, and the waves. The rhythm of these linked elements evokes a kind of relationality, a sense of things moving or working together, which by all means feels as though it should be a comforting framework. In the context of the poem which bears this line, however, this relationality becomes alienating, distracting, a network of elements which cleaves to the logic of the dream and excludes the speaker of the poem. She is not comforted; instead, she stands at the edge of the water which has swallowed her sisters and left her alone, abandoned or lost or too slow to keep up. “[M]y sisters are gone, they’re / somewhere beyond the break,” Clayton writes, “they’re there / they’re there, they must be” (18). There is a caveat, however, as there always is in dreams where nothing is as easy as it seems: “But the sun, and / the ships, and the fish, and the waves” (18). The network of the dream separates the speaker of the poem from the dreamt form of her sisters; the relationality of the world isolates where instead it ought to extend comfort.

Dreams, after all, are liminal spaces where thinks we take for granted begin to shift. Time, certainly. Form, absolutely. Even death can be reversed in dreams, or, alternately, put into fast-forward. Clayton confronts her dead mother, chases her sisters through shifting landscapes, runs from faceless men who seek to enact unnamed violence upon her, slips through time like water: “My sisters and I are children, / playing in the empty lot. I recognize our hair / in the tall grass. I’m your future self, I yell” (20). No one hears her, of course, and once again the speaker of the poem is caught on the outside of the dream’s world, unable to affect its narrative in the way she so desperately wishes she could.

The logic of the dream, of course, is informed—or perhaps undercut—by the reality of the waking world. Some pieces in the collection bend more easily than others, becoming complicated by curious addendums which appear on the following page of the original poem. These interloping stanzas break with the paragraph-prose-poem style of the rest of the book, and their forms—spreading like dandelion seeds in summer air or cracks in old glass—often hint at further evidence at the violence at the heart of these poems: “My mother at / the top of the / stairs” reads the first coda in this vein (16), describing a moment in which something ominous feels imminent; “His body / pushed / against // mine // in the / bathroom // while / people walk / by, clueless” reads part of the next (24). Perhaps this violence slinks into the dream from above, from below—that is, from the real world. Or is it the other way around? Might this striking-out resist the dream world and rewrite its logic, affirming the comfort of reality in which the dead stay dead and past violence remains past?

Dreams are a kind of haunting, after all—only here the poet becomes the ghost. She is troubled by objects that refuse solidity, stymied by expectations of time and interaction, made desperate by the distance that opens up, unannounced and unwanted, between her and the living spectres of those she seeks to protect. “Everyone else is scared, but I enter the water,” Clayton writes, even as she admits: “I know my flesh will / rot but I trust that toothless mouth” (47). If there is a cost to be paid, she is willing to pay it; no dividing abyss of space or absence is enough to deter her from her task.

And yet, Clayton writes, “I don’t miss the missing parts of me” (59). In other words, perhaps, what can really be salvaged from this landscape of a dream, even muckraking as it is through the poet’s subconscious? Can anything be brought to the surface, or should lost objects and moments instead remain lost? On one hand, these poems argue that the revelation sought in dreams is only ever shrouded with obscurity, and yet so too do these dreams create bright spots of hope and wonder and surety that may later transform into gates, into egress.

From beginning to end, Clayton’s dream world remains kaleidoscopic, as ominous and cheerful as a circus or a surrealist painting. Still, the speaker in the poems remains determined, hell-bent on survival, protection, revenge. There is meaning everywhere, these poems seem to say, if you are willing to dowse for it. Or, in other words, as Clayton’s dream-self croons to a deer in a field: “I know / my hand seems empty but I’m telling you it’s / not” (44).

This review was assigned before Conyer Clayton joined Canthius as Social Media Coordinator.

Dessa Bayrock lives in Ottawa with two cats, one of whom is very loud and almost always nearby. She used to fold and unfold paper for a living at Library and Archives Canada, and is currently a PhD student in English, where she continues to fold and unfold paper. She has two chapbooks with Katie Stobbart: The Trick to Feeling Safe at Home (Coven Editions, 2021) and Worry & Fuck (Collusion Books, 2021), as well as one with just her poems about bad dreams (Is It About Ruins and Ghosts?; Ghost City Press, 2019). She was the editor of post ghost press for nearly three years and was the recent recipient of the Diana Brebner Prize. You can find her, or at least more about her, at www.dessabayrock.com, or on Twitter at @yodessa.