Blue and Red Thread: Review of Light Years by Laboni Islam and militant by Jody Chan

In the fall of last year, Baseline press debuted a new poetry line-up of four chapbooks, including Laboni Islam’s Light Years and Jodi Chan’s militant. I am lucky enough to sit down with these two works and explore their intermingled threads.

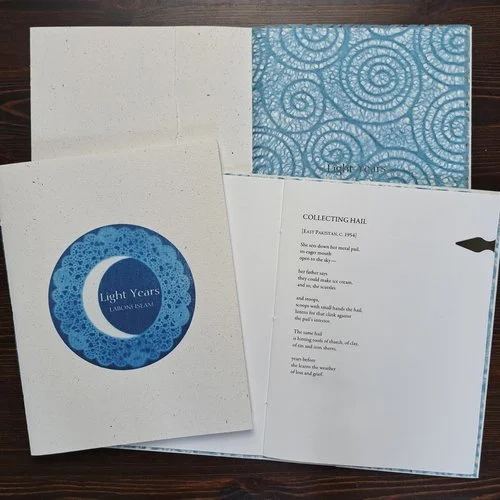

Laboni Islam, Light Years.

Baseline Press, 2022. $13.50 CAD.

Order a copy from Baseline Press.

Light Years by Laboni Islam starts with an acknowledgment: “for my family, in memory of my father.” The relationship between the speaker and their family is imbedded in every facet of this collection, manifesting sometimes in direct address: “Sister, in lunar year/ we are older,” (“Counting”), sometimes in an embodied centering: “My mother assembles frames into a horizon called father. The Moon reflects the light of four sons/ one daughter.” (Lunar Landing, 1996”). Love oozes from every page of this chapbook. The poems run both horizontally and vertically, as if the speaker is using every available inch of space to express their tenderness.

Light Years’ love language is sharing moments of quiet, private warmth. We see the subjects of this collection at their most tender. Sometimes these moments are quotidian: “I miss the slow shuffle of your slippered feet” (“Wake”), sometimes achingly expansive, like in “Meteors:”

When Pluto was a planet,

my father reclined

beneath the dome of the planetarium,

ceiling so vast,

it contained the universe,

wanting, I think,

to understand his place in it,

trace the arm of God’s compass

back to its centre. We never spoke

about depression,

Each of these moments is a perfect liminal capsule. Time and space fall away. The “when” does not matter, only the memory, perfectly preserved. Like the speaker in “Second Generation,” who falls asleep in the rickshaw between houses, we are invited to find comfort in transition.

While these poems centre others, at its heart the collection is based in the self. Moments of stillness make up the sum of the whole, most notably in “First Snow:”

It settles

The way I never have,

into crooks and furrows,

solitary crystals

sticking together. On this eve

of a citywide lockdown

The speaker’s loved ones are not with them in the room, but always orbiting. Always peripherally present. In Islam’s acknowledgements, she writes “My mother, who is and always has been a poem.” Indeed, familial love makes up the very essence of the work.

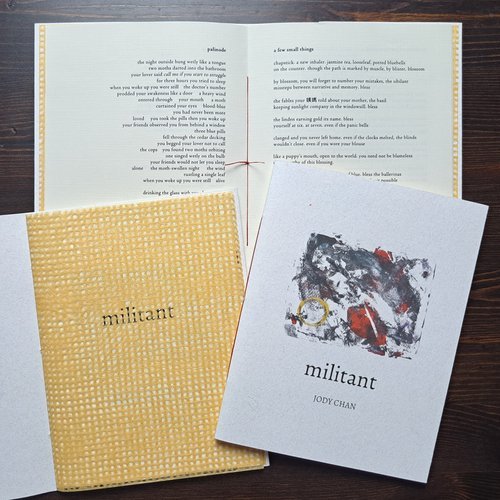

Jody Chan, militant.

Baseline Press, 2022. $13.50 CAD.

Order a copy from Baseline Press.

Like in Light Years, Jody Chan’s militant concerns itself with stillness. The chapbook begins with a Johanna Hedva quote on revolution: “Perhaps it looks something like the world standing still because all the bodies in it are exhausted.” The collection is divided into three sections: “how to survive,” “how to stay,” and “how to refuse.” As each section is introduced, the back of the page is left blank, showing the imprint of the words through the linen paper. There is a feeling of coming to peace with stillness, of allowing a moment to linger, and not rushing for change: “I can love the distance/ between us/ I can.” (“stay at home order”).

Like the subtitles suggest, this collection reads often like a guide. Sometimes for the speaker: “to fill the prescription/ to stockpile inhalers/ to arrange rotten avocado on toast” (“how to survive in a time of great urgency”), and sometimes a guide for the reader. Chan often utilises direct address to immerse. Whether the “you” is you, or me, or the speaker, or someone else entirely, does not matter. In these moments we are all mushed and meddled together, all in the same room:

bless the ballads filled with shades of blue. bless the ballerinas

leaves make of themselves in November. consider it possible

that you, too, are beloved. simple as that,

that for someone in this life, you are a balm. a ballast. (“a few small things”)

These moments of community are themselves an act of resistance. To find ourselves with each other when we are apart. To look at the other faces in the Zoom call and not your own little box: “I focus on keeping the house plants/ warm. I call you on the screen and I try/ to make eye contact.” (“stay at home order”).

In militant, objects are sacred, their presence or absence is worth taking note. We come back to lists as a way of anchoring, always in tune with the space: “chapstick. a new inhaler. jasmine tea, looseleaf, potted bluebells/ on the counter.” (“a few small things”). Colour anchors as well, as the speaker or subject isolates from or aligns with it:

tired of loving blue

from afar she entered it making heaven (“Qingming”)

The “you” is a balm for someone in “a few small things,” the objects are a balm for the subject, the book is a balm for the reader. The resistance is in the stillness, in the quiet listing and consolidating, in the leaving and the returning.

Just as objects are sacred in militant. Baseline’s chapbooks are, as always, striking to behold. Designed by Karen Schinder in collaboration with the poet, each chapbook is printed on linen paper with a vibrant flyleaf; Islam’s a warm spiralling blue, mirroring the moon and it’s orbit, Chan’s a vibrant gridded yellow, reminiscent of a picnic blanket for a spread to be displayed. Each book is bound in the centre by a coloured thread, marking the midpoint of the work. Islam’s blue, Chan’s red, both gorgeous to hold and explore, the paper its own visceral experience. As both a sacred object and brilliant poetic work, neither of these chapbooks are to be missed.

Olive Andrews (she/they) is a writer living in Tiohtià:ke (Montréal). Their poetry, reviews, and articles have been published in Canthius, Arc Poetry Magazine, PRISM international, and elsewhere. Their debut chapbook, rock salt, was published with Baseline Press in 2020. TERRIFYING FRIENDS, a collaboration between eight poets, is forthcoming with Collusion Books in 2023. Find them at their website: oliveandrews.ca