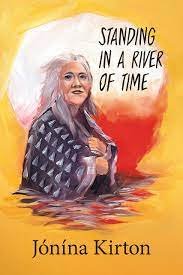

Much to let go of in Jónína Kirton’s Standing in a River of Time

Jónína Kirton, Standing in a River of Time.

Talonbooks, 2022. $19.95 CAD.

Order a copy from Talonbooks.

Standing in a River of Time by Jónína Kirton is an unrelenting memoir. Each chapter is comprised of a narrative section and a set of poems, focalized through a character, theme, time frame, or a series of events. It is also a heavy text, holding stories of death, abuse, violence, intergenerational trauma, and poverty. The prose offers gritty details that form narrative and context, and the poems revisit those stories with lyrical indulgence, often grasping for interstitial positions — between feelings, spaces, and possibilities. Kirton’s voice is gentle but steady, addressing contradictions with an earnest droll: “The mixed-message queen that I am is wanting to look good while wanting to die, while hunting men, while being the most spiritual person in the room” (65), while also making room to be tender and pragmatic — a posture she takes up when meeting the events of her own life.

The book’s title declares Kirton’s intent to bear witness to herself: in pause, in preparation, in resistance. She gestures to her body repeatedly as the site of violence and trauma, but also of agency and transformation, declaring herself “the daughter of a shapeshifter” (52) in an early poem “I Am.” She then moves through shifting relations with family, lovers, teachers and friends, grappling with agency, identity and history, to emerge on the other side of the pages declaring “my body a universe” (191) in the poem “All My Relations.” As the book wanders through decades of life, Kirton always returns the focus to herself as a bodied narrator, to “stand,” so to speak, in and for herself.

Kirton also stands in the world, as all personal history is inevitably also about larger histories, seen and unseen, known and unknown. Those other histories can bring solace because they are so much bigger and offer us orientation to navigate our circumstance, but they also arrive with a magnitude that we cannot always handle. Kirton moves through the contexts of what it means to be Métis and Icelandic, to live and make home on this land with its violent histories, and how these contexts touch every aspect of living: bodied, spiritual, material, relational, writing:

“The bones of my Ancestors

How they pull on me offering so many directions

Yet how can I answer the many folded inside my body?

this body not my own a shared place of suffering” (Kirton 40)

The conflict of being pulled in many directions appears as a formal tension as well. Kirton’s poetry is at times rough, more of a work-in-progress than finished work:

“we know that

feelings cannot make their way across the web

but some empaths and poets find ways

to make the distance shorter

while others offer to teach us

how to meditateto become fortunate via podcasts” (128)

There are also certain gestures I find jarring, such as when Kirton takes concepts and objects from various Asian cultures: a popular quotation attributed to nüshu text that opens a prose section (155); an anecdote of her placing buddha figures she refers to as “altar items” around her home (136); her use of “Saṃsāra” as a poem title (83). These moments of borrowing seem at odds with the refreshing candour of her negotiation with un/belonging as a Métis. There, she demonstrates great compassion and reflexivity around the difficulties of navigating identity violently erased and obscured; recovered in parts, with great messiness, by a diverse group of people. In unpacking her Icelandic and Métis lineage, it is evident that cultural inheritance is not a matter of unearthing anything “essential”, nor is it the agency to just pick and choose the parts that fit you. Things exist in context and relation, through elders and community, passed down in ritual, and mutual understanding. By contrast, Kirton’s borrowing of Asian concepts and images to narrate her story feels uncritical and orientalist.

This act of stitching a life together from disparate things, however, is a strong throughline of Kirton’s journey toward power and agency, perhaps in defiance of, or making peace with being pulled in many directions. Kirton writes that “those who live on shifting ground / take their poetry seriously” (173), but what she is referring to, is “uncredited text” decorations in an Icelandic washroom. That this is the poetry to take seriously is a humorous wink, but she also means that poetry can be found anywhere, even in mass-produced quips. It reflects the spirit with which Kirton tackles her stories, banal details reminding us that what makes a life are its days piled into a messy mass. This book retrieves those details like stones. It examines. It puts down. There are stones turned and unturned everywhere. They are the shifting ground of Kirton’s life.

Standing in a River of Time is not interested in standing alone — it is Kirton’s recognition of her abundant relations, and an invitation to the reader to engage with her. The events, emotions, and stories of these pages make up the messy landscape of what it looks like to hold and heal. They are addressed prosaically and barefaced, in meter and verse, in image and metaphor. They are returned to and revisited in subsequent chapters; they become part of other stories even if no longer the focus. In reflecting Kirton’s journey, the text moves like a spiral, returning and returning, telling us “there is always so much to let go of” (189) and yet, also flowing forward, “letting go of shame, one little piece at a time” (186).

Jasmine Gui is a Singaporean-born interdisciplinary artist, and arts programmer based in Tkaronto. She works out of Teh Studio and San Press in text, mixed media, and tea mediums. A member of TACLA, a pan Asian documenting commons, she also collaborates on experimental paper arts as one-half of creative duo, jabs. She is currently a PhD student at York University.