Review of ZOM-FAM by Kama La Mackerel

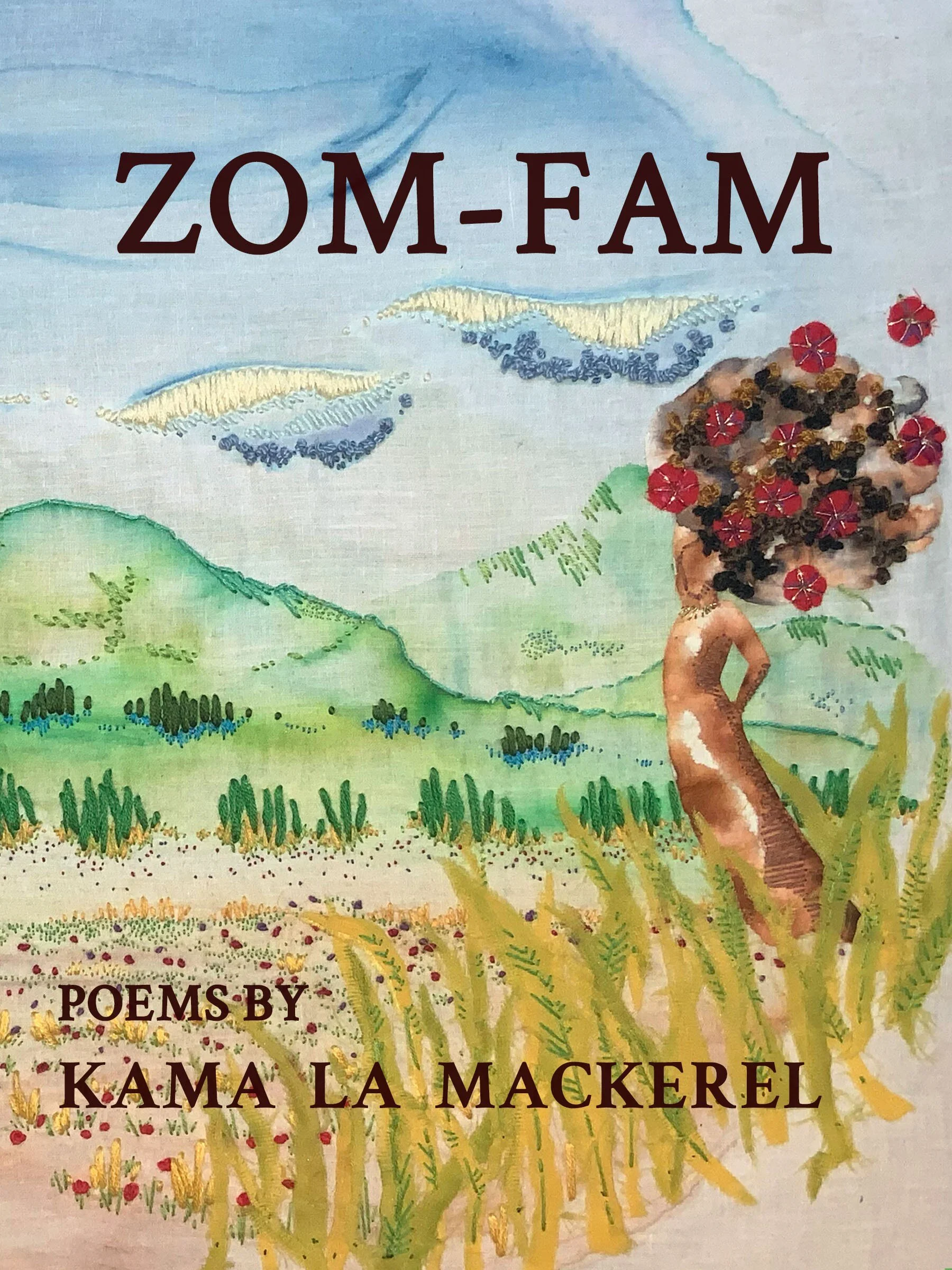

Kama La Mackerel, ZOM-FAM

Metonymy Press, 2020. $16 CAD.

Order a copy from Metonymy Press

In their debut poetry collection ZOM-FAM, Kama La Mackerel interweaves mythology, biography and colonial history in a queer and trans narrative rooted in their native island of Mauritius. This is a story about being and becoming, about creating vocabularies for yourself and stepping into them as you would a home. La Mackerel has wrought such a vocabulary for this collection, one that is tender and honest, that defies the boundaries of the English language.

ZOM-FAM comprises eight long-form lyric poems that map the journey of the speaker’s body across oceans and gender. In the first poem, the speaker invokes “the bloodlines of women & femmes / whose bodies are steep with the darkness of the kala pani” (3)—and though they are silent for the rest of the book, they linger in the margins, in the spaces carved “for your queerness / to survive” (45). They are present on the ill-omened day when the speaker is born, a “zourne mofinn” (which roughly translates to “day of bad luck” in Mauritian Kreol). These inheritances, whether they are names, traumas, dreams, or silences, define the speaker.

But if the speaker exists in and is shaped by a tradition of femme tongues and ancestral voices, so too does their father inherit a legacy of colonial silence – silence that yawns across the page and distances father from queer femme child. Watching their father build their house for twenty years, the speaker observes that their father speaks

in the language of men

who were forced

to cut out their tongues

. . .

their silence

a stout echo (36–37)

This paradox of distance, of sharing a home and a history with someone yet still circling one another like travelling stars, is an especially powerful way of articulating the speaker’s relationship with their father. That said, I wonder whether the spaces between the words, meant to evoke “the distance between our bodies . . . the distance between the words we exchanged” (37), hold the same emotional weight as silences might in a spoken performance of the same poem.

In ZOM-FAM, gender is both a threat to survival and safe harbour on the plantation island. La Mackerel carefully carves this liminal space between the father’s unyielding, brick-like masculinity and the mother’s tender femininity. We are constantly on the edge of “coastlines / of being, longing / belonging” (45). This interstice is evoked in the Mauritian Kreol word “zom-fam” that the speaker defines as “a man-woman being neither zom nor fam / yet being both zom & fam” (89). It is

an undefinable space that maps the cartography of my skin

a hyphen that holds & wraps my gendered experience (89)

For the speaker, “zom-fam” (meaning neither man nor woman, but still both man and woman) is an undeniably political term. Some of the most evocative writing in the collection is La Mackerel’s description of this word, this concept, this way of being for which there is no equivalent in English. It is a demand to be understood on the speaker’s terms, independent of English and other imperial languages, remnants of French rule in the 18th century and later British rule into the 19th and 20th centuries. And although the speaker is educated and knows English and French, they also have within them:

a voice that does not have the words or the vocabulary

but reverberates goodness & music in my body—

. . .

like the waves of the oceans

that witnessed

the loss of our languages (93)

It is this motif that echoes throughout the book: to speak even as language is lost, to make poetry despite the silence enforced by colonial rule. This book is a process of being and becoming—from having “a story scripted for your body” (43) to actively declaring, and in doing so reclaiming, that this body is to be called “zom-fam” (95). ZOM-FAM, the Kreol word and La Mackerel’s collection, is a decolonial way of moving through the world.

Bridget Huh is in her first year studying English and Creative Writing at Concordia University. She is based in Toronto and rides her favourite bus routes back and forth in her spare time.